More about the history of Vesledalssetra

The history of Vesledalssetra goes far back in time. Remains of Stone Age tools have been found just east of the Vesledalsbreen glacier, near Austdalsvatnet. This shows that hunting was carried out in this area more than 6,000 years ago. At that time, the Jostedalsbreen glacier had melted away, and the easiest route to the area ran through Erdalen and Vesledalen.

Archaeological excavations and finds show that there were several settlements in Oppstryn during the Bronze Age—more than 3,500 years ago. Pollen samples indicate that grazing livestock were present in the mountain pasture valley at that time.

In the earliest period, the seter was located on a large open plain further up Vesledalen, known as Seltuftene. Investigations suggest that there was probably a mountain pasture here before the birth of Christ.

In 1898, a land reallocation of the mountain pasture valley took place. Tjellaug and Greidung were then assigned Vesledalssetra, while the other farms in Erdalen received Erdalssetra. A brushwood fence/stone wall was built as a boundary between the pasture areas.

Briefly about mountain pasture farming

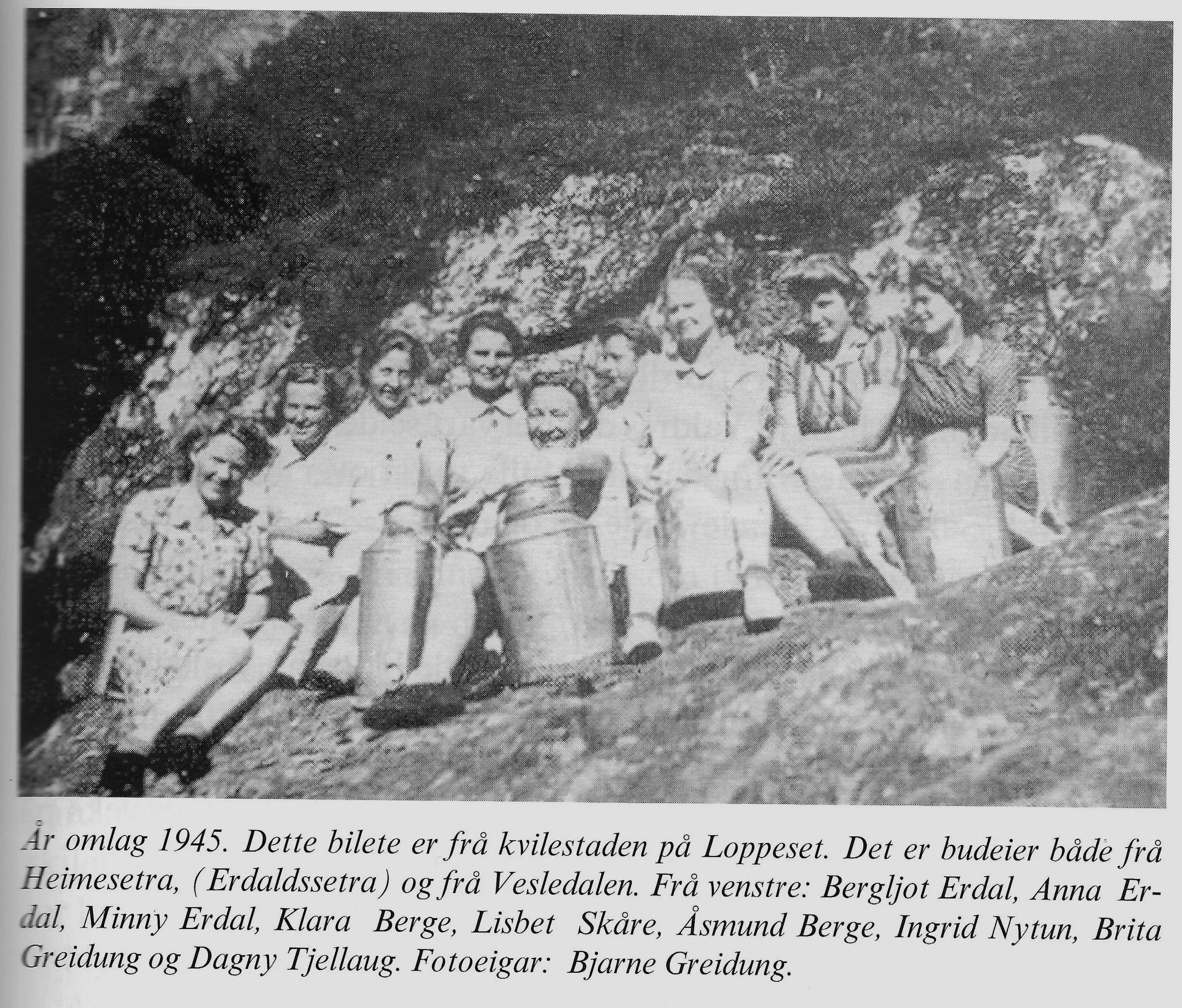

After the reallocation of pasture rights in 1898, six farms held grazing rights at Vesledalssetra: two farms at Tjellaug and four at Greidung. Until the late 1920s, both cows and goats were kept at the pasture. Some of the farms joined together to hire a dairymaid who stayed at the seter throughout the summer. She milked the animals, made cheese, and churned butter. The farmers who employed her took turns carrying food up to the seter and bringing the dairy produce back home.

Most farms had a girl or boy of suitable age who could milk the cows. They walked up to the seter every afternoon, milked the cows, and placed the milk to cool in a trough. They then had a short rest before it was time to go to bed. Early in the summer they had to rise very early, often around three or four in the morning. As daylight broke, the cows grew restless, eager to leave the cowshed to find good grazing.

After the morning milking, all the milk was poured into a specially made milk container, which they carried on their backs back down the valley. They arrived home just as people were beginning to get up, then slept for a couple of hours before joining the day’s work. When the clock approached five in the afternoon, it was time to set off for the seter again. They often walked together with girls and boys heading for Erdalssetra.

There was a strong sense of community among those who went to the Vesledalsseter to milk the cows, and they shared many enjoyable moments together. Today, few remain who experienced this way of life.

The photo is taken from the book “Setrar i Oppstryn og Nedstryn” by Kjell Råd.

Seltuftene

Seltuftene is an open plain that you cross when walking from Vesledalssetra towards the Vesledalsbreen glacier. The walk takes about fifteen minutes. Remains of old mountain dairy buildings have been found here, and it is believed that the summer farm was originally located at this site. Charcoal fragments and burned bones have been discovered, indicating that there was a summer farm here before the birth of Christ (Fure 2011).

Pollen analyses at Seltuftene show that the tall-herb forest disappeared already in the Bronze Age, which suggests that grazing took place here at that time.

It is uncertain when the summer farm was moved to its present location, and what the reasons for the relocation were.

Cattle trading across the glacier

Most of those engaged in cattle trading in Nordfjord came from Jostedalen and Luster. In the late winter after Christmas, cattle traders crossed the glacier on skis to make agreements with farmers for the purchase of livestock—mainly cattle, but also horses and sheep. They returned in June to gather the animals and drive them toward the final assembly point before the glacier. The animals had to be driven from Vesledalssetra before Midsummer (St John’s Day), as the farmers of Erdalen then brought their own herds up to the pasture.

Tor A. Greidung and his son Rasmus T. Greidung served as record keepers. They noted the number of animals driven across the glacier from Vesledalssetra to Fåberg toward the end of the 19th century. In 1890 there were three cattle chases totaling 153 head of cattle, seven horses, and 300 sheep. The largest cattle chases took place in 1886, with 147 cattle and seven horses.

The last cattle chase across the glacier from Vesledalssetra probably took place in 1920 (K. Berge, 1961). After that, it became difficult to access the glacier with cattle.

The cattle traders chased the livestock herds over the mountains as far as Drammen, or south to Bergen, where there was demand for meat. Some of the animals were sold as breeding stock.

Stone Age Finds

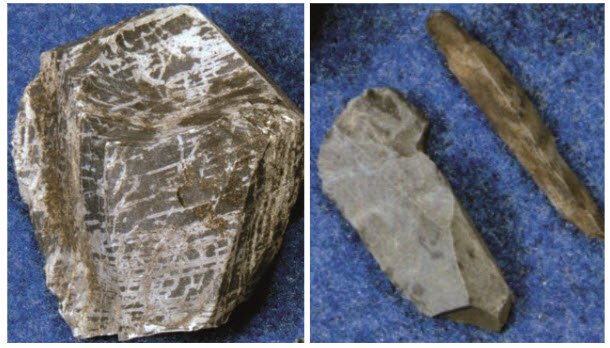

Several cultural heritage sites have been recorded that show people have stayed at Vesledalssetra for thousands of years. At Austdalsvatnet, east of the Vesledalsbreen glacier, finds from the Early Stone Age have been made, clearly originating from the coast.

The materials discovered include diabase from Stakaldeneset in Flora and Siggjo rhyolite from Bømlo. At both of these locations there were long-standing quarries where raw materials were extracted for stone axes (diabase) and for arrowheads, knives, and scrapers (rhyolite).

This indicates that people travelled through Strynedalen in prehistoric times (Randers 1986). The shortest distance from the head of the fjord to Austdalsvatnet is through Erdalen. We know that the Jostedalsbreen glacier had melted away during the period 7,500–6,000 years before present (Nesje and Kvamme 1991).

Rekonstruksjon av ei diabasøks av Morten Kutchera

Siggjo-rhyolitt

This provides the basis for claiming that there was travel from the coast up through the Stryn river system in prehistoric times, more than 6,000 years ago (Randers 1986).

Glaciologists believe that the Jostedalsbreen glacier had melted away during the period 7,500–6,000 years before present (Nesje and Kvamme 1991).

Cultural Heritage

Map showing the different sites

Charcoal layer. Lies beneath 10 cm of turf and soil, measuring roughly 2–4 cm thick. Covers an area of 4 x 5 meters. Dated to the Iron Age–Middle Ages. Indicates charcoal production.

Site with two charcoal pits used for producing charcoal, and two charcoal layers. The pits measure approx. 1.30 meters in diameter and 30–40 cm deep. One of them is dated to around 500 AD.

Two charcoal layers at a depth of 20 cm beneath 5–7 cm of turf. Dated to approx. 800 AD. Indicates charcoal production. Date: Late Iron Age.

Large boulder with an overhang facing the river to the west. Soil containing large amounts of charcoal fragments at a depth of about 8 cm, both outside and beneath the drip line. Date: Middle Ages.

Large boulder with an overhang facing west. The area beneath the drip line is 2–3 square meters. Test pits revealed brownish soil with charcoal fragments at a depth of about 10 cm. Date: Iron Age–Middle Ages.

Large boulder with an overhang. Opening facing southeast. The opening is tall enough to stand in and extends around 3 meters deep. Test pits showed a thick charcoal-rich layer from 0–6 cm. Date: Middle Ages (1030–1536).

Dwelling Places Beneath Overhanging Stones

Charcoal was discovered beneath a large boulder at Vesledalssetra. The boulder has an overhang with space for several people inside the drip line. The find is dated to the same period as the Bronze Age settlement in Mykjedalane near Hjelle – more than 3,000 years old.

Pollen analyses from the summer farm area also show the earliest signs of human activity in this period (the DYLAN project).

The large boulders with overhangs are ancient cultural heritage sites. They were used as dwelling places far back in time, likely by people travelling through the area or by those staying near the summer farm in connection with hunting, grazing, or other activities on the mountain pasture.

You can see this boulder when you enter the summer farm meadow. There is plenty of space beneath the drip line. See cultural heritage site no. 6 on the map above.

A short distance below the summer farm meadow you can find this hollow beneath a large boulder. It provides good shelter from wind and weather.

Charcoal Production

Several charcoal pits have been found. These were used in the production of charcoal, which was essential for extracting bog iron and for forging iron tools. Wood, probably birch, was stacked in the charcoal pit. It was then covered with turf and soil and set on fire. Controlling the temperature was crucial. At the right temperature (around 270°C), the wood was transformed into charcoal.

Charcoal layers may represent areas where charcoal was produced using charcoal mounds. In this method, the wood is stacked above ground.

The image above shows what a charcoal pit can look like in the landscape after being out of use for several hundred years.

Sources

- Kulturminnesok.no

– Erdalen and Sunndalen: Use of grazing resources for more than two thousand years. NIBIO Report 8, No. 139, 2022

- Internet.

Text: Asbjørn Berge, 2025

Photos: Marit and Asbjørn Berge